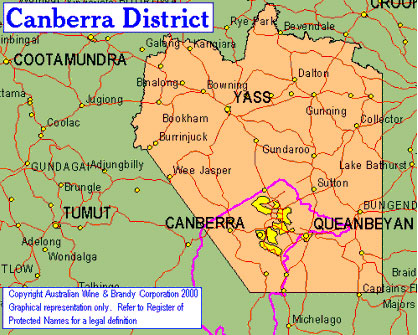

The Australian Geographical Indication “Canberra District” was entered in the Register of Protected Names on 9 February 1998 in response to a direction received by the Registrar from the Presiding Member of the Geographical Indications Committee acting under Section 40Z of the AWBC Act 1980.

To a large extent, the emergence of the Canberra District can be seen, as described by Nicholas Faith in his 2002 book “Liquid Gold” when discussing the making of good wine more generally, “as a result of geology, geography, history and the sheer bloody-mindedness of some key individuals.”

Brian and Janet Johnson’s ” Wines of the Canberra District – Coming of Age “ addresses each of these essential features of the District’s development and below is an extract from Chapter 6 of that book which deals with ” Climate, Soils and Viticultural Practices in the Canberra District.” We are grateful to Brian and Janet for allowing us to reproduce that material here. For further information on ” Wines of the Canberra District – Coming of Age “, which is an updated and expanded edition of a book first published in 2002, visit www.mckellarridge.com.au.

Chapter 6 – Wines of the Canberra District – Coming of Age

Climatic Conditions

The cool climate of the Canberra District is proving to be a key success factor for the grape growers and winemakers of the District.

It is a highly continental climate, with a large difference between the average mean temperatures of the coldest and hottest months (Gladstones 119: 15). Gladstones cites the work of Gadille in Burgundy, where the seasonal characteristics that most clearly distinguish the best-quality vintages are high mid-summer temperatures and high sunshine hours—both key features of the climate of the Canberra District. As Gladstones (op. cit.: 17) notes, however, continental climates are also notoriously variable. The timing of perfect ripening conditions can be precarious in such climates.

While the early pioneers of the 1970s struggled to successfully establish grapes in the Canberra District due to a combination of droughts, pests and spring frosts, current growers have access to improved technology that is making a considerable difference. The use of drip irrigation to assist vine establishment during the dry, hot summers that occur in the District has proven to be essential, and some early frost-prone sites have now been abandoned or the vines grafted to later-budding varieties.

Careful site selection now allows growers to select those sites that have good cold-air drainage to minimise frost problems, and modern spray technology provides effective control of weeds, pests and potential mildew and Botrytis problems. This modern experience contrasts with the somewhat pessimistic views expressed by Dr John Gladstones in his seminal study of the environment and grape growing undertaken in 1992. At that time, he saw little potential in the Canberra District because of the hot summers and frost susceptibility of the region (Gladstones 1992).

Major positives are the high number of sunlight hours, with the mean annual temperature in summer of 20ºC in January, and the long, cool autumns, which produce grapes high in flavour with excellent acid/sugar balance and opportunity for maximum flavour development. Good dryland yields of 5–8 t per hectare are now achievable in mature vines, producing fruit of excellent quality.

The autumn conditions are what provide the opportunity for grape ripening that produces intense flavours and hence special wines. The region usually is subject to ‘cold snaps’ during February or early March, about four to six weeks before harvest. This is thought to cause a buffering effect on the pH levels in the grapes by maintaining malic acid in the grape and, in practical winemaking terms, results in low pH grape juice with good natural acid levels at harvest—a factor strongly preferred by winemakers. The long, cool, generally dry autumns also allow the harvesting of the grapes when flavours are maximised and sugar/acid balance is optimal.

Gladstones (op. cit.: 30) also notes the benefits of coastal sea breezes on grapevine photosynthesis and physiological ripening of grapes. While the Canberra District is more than 200 km from the South Coast of NSW, it often benefits from late-afternoon easterly coastal breezes during summer and autumn, which cool the vine and assist development of the grape.

Temperature Comparisons with Other Wine Regions

Various attempts have been made to “classify” different grape-growing areas using temperature summation techniques in order to identify suitable growing areas.

Dr John Kirk from Clonakilla was instrumental in adapting an early system of this approach, developed by Amerine and Winkler at the University of California in the 1940s, and applying it to the Canberra District (Kirk 1986, 1987).

The temperature summation approach applied by Dr Kirk uses the following formulae. The average daily temperature for each of the growing months (October to April in the southern hemisphere) is summed, subtracting 10ºC (as grapes do not grow below this temperature), multiplying by the days in each month, for each of the seven months to give the temperature summation in (effective) day-degrees.

Dr Kirk then classified the day-degrees categories:

- 901–1200: Cool

- 1201–1500: Mild

- 1501–1800: Warm

- 1801–2100: Hot

- 2101–2400: Very Hot.

The Canberra District, under this classification, fits mostly within the Mild category, with average 1400 day-degrees. This is comparable with the Bordeaux region of France, the northern end of the Rhone Valley and the Coonawarra region of South Australia. Important differences emerge in this general picture, however, when differences across the region and altitude effects are accounted for.

Helm and Cambourne (op. cit.) established that some years can be regarded as “cool”, with 1300 cumulative degree-days, and others as “warm”, with greater than 1500 degree-days. In cool years, the climatic conditions typically suit the early season varieties such as chardonnay, pinot noir and sauvignon blanc. Warmer years favour cabernet sauvignon and shiraz, when the additional warmth allows full ripening of the later-maturing grape varieties.

A comparison of cumulative degree-days for the Canberra District with other major grape-producing areas in Europe by Helm and Cambourne revealed:

- 44.6 per cent of years in the 1301–1500 range of degree-days comparable with the Medoc and Sauterne (Bordeaux) regions of France

- 32.1 per cent of years over 1500 degree-days, more comparable with the Hermitage (Rhone) region of France

- 23.2 per cent of years fall in the cooler range of 1000–1200 degree-days, comparable with the Champagne, Chablis and Graves regions of France.

ERIC Analysis

Environmental Research and Information Consortium Proprietary Limited (ERIC), based in Canberra, undertook a detailed analysis of the climate, soils, rainfall and frost hazards in the southern NSW region, under commission from the ACT Government.

Temperature Comparisons

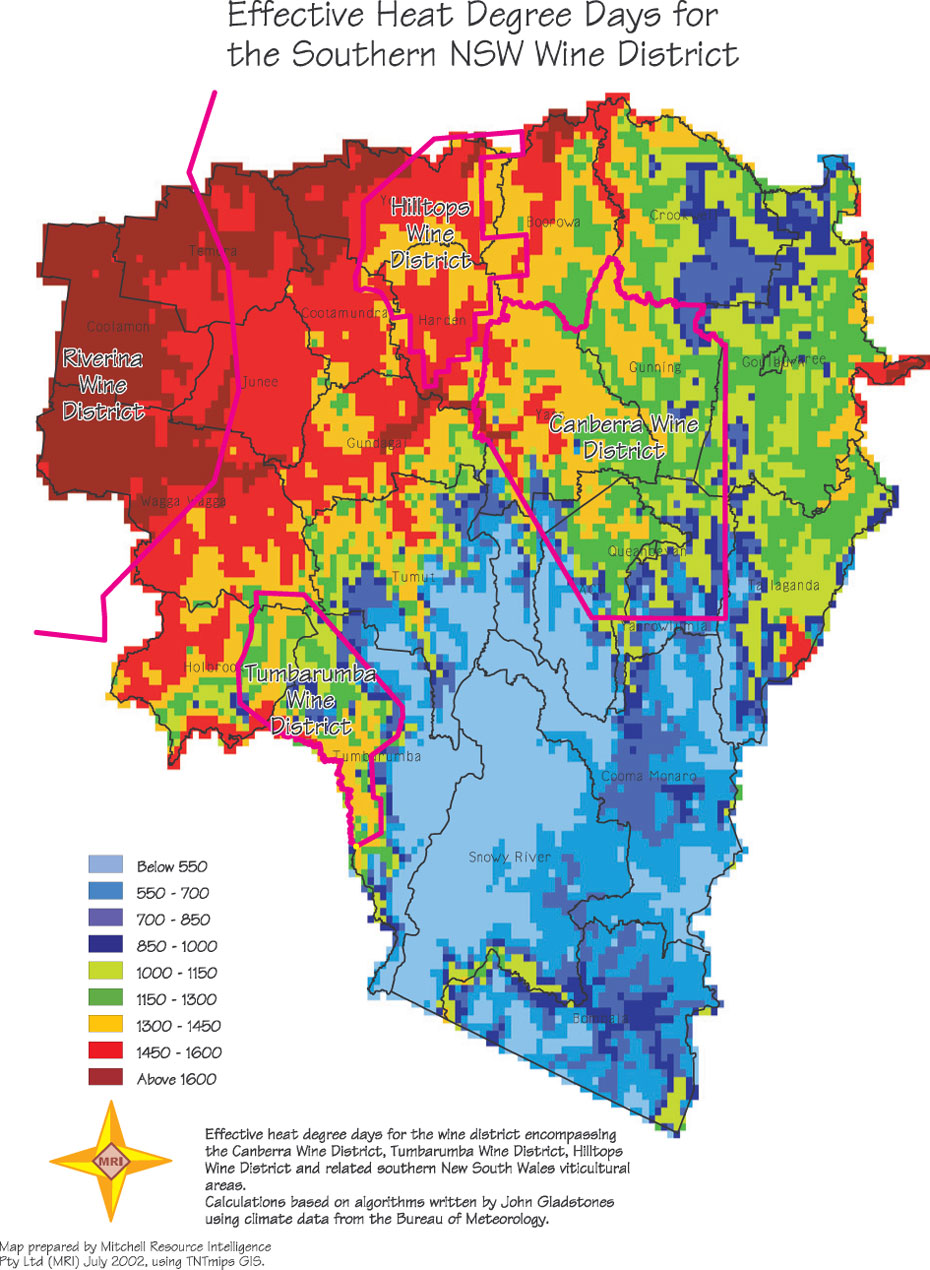

Using the work of Dr John Gladstones, ERIC estimates Effective Heat Degree Days (EHDD) as a measure of the amount of heat required to bring different grape varieties to maturity. EHDD below that required by different varieties will result in unripened fruit (excessively acidic and with little fruit flavour) and EHDD in excess of that required can result in loss of fruit balance, with excessive sugar levels and low acid levels. Good-quality wines require fruit balance and great wines require fruit balance and maximum flavour potential. Experience is showing that the latter occurs in “cool-climate” regions where conditions allow fruit flavours to be maximised and fruit balance to be maintained.

Map 1 shows the EHDD distribution for the southern NSW region, encompassing the Canberra District. The areas to the south of the Canberra Wine District are generally too cold for grape growing, except for small pockets of country in valleys. The area to the west is suitable, ranging from 1000–1300 EHDD in the Tumbarumba region through to 1600 EHDD and above in the west, around Cootamundra and Junee. The Hilltops region has warm–hot grape areas in the 1300–1600 EHDD, depending on elevation. In the east, the area around Goulburn has extensive areas within the cool-climate range.

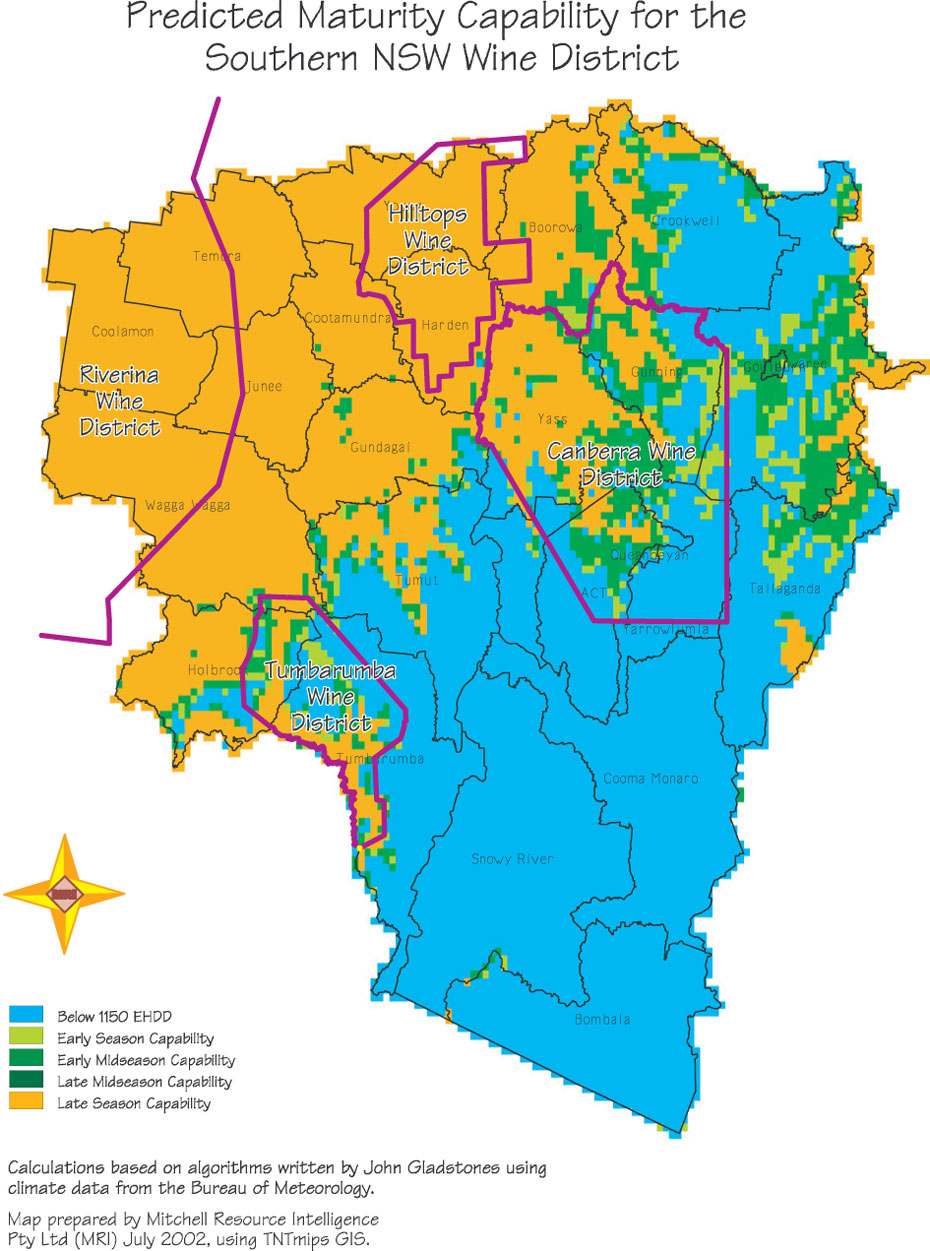

ERIC has plotted the suitability of the southern NSW region for different grape varieties using the EHDD approach.

EHDD varieties are classified as:

- Early Season (1150 degree-days required)—includes chardonnay, malbec, pinot noir and sauvignon blanc

- Early Midseason (1200 degree-days required)—includes cabernet franc, merlot and semillon

- Late Midseason (1250 degree-days required)—includes cabernet sauvignon, riesling, shiraz and viognier

- Late Season (1300 degree-days required)—includes grenache, marsanne and mourvedre.

Map 2 presents an analysis of the predicted maturity capability for the southern NSW wine region. In general, the early season varieties are suited to the cooler, higher sites—mostly to the east—and the late-season varieties to the warmer north-west. The central zone that includes the Murrumbateman corridor has many sites suited to mid-season maturity varieties.

Another interesting variable is the altitude choice of the region’s vineyards. These range from 500 to 860 m above sea level, with the highest in the District being Lark Hill near Bungendore. At these altitudes, some restrictions on ripening of later-maturing varieties can occur, whereas at 500–700 m—typical of Murrumbateman, Hall and Lake George vineyards—such restrictions are not usually a constraint.

Rainfall

Annual rainfall for Canberra is 635 mm per annum, with some variation across the Canberra District, generally in the 600–800 mm range. The monthly rainfall is quite evenly spread across the year, with some winter dominance. Evaporation rates are high during the summer months, far exceeding available rainfall.

Rainfall during the winter months, when evaporation levels are low, usually recharges the subsoil, providing a supply for the growing season. The experience of the pioneers—particularly Dr Edgar Riek and Dr John Kirk—was that young vines require supplementary drip irrigation during their establishment, as the summers are hot and dry and droughts are not uncommon.

The autumn weather pattern is usually stable, providing good conditions for final ripening and harvesting. This minimises the chances of bunch rot and mildew, which can be a problem in other climates, particularly Europe. In a wet autumn—as occurred in 2010—rainfall can disrupt harvesting and requires early harvesting to avoid excessive losses due to disease.

Water Requirements

As noted, high levels of evaporation during summer can cause vine stress, and in some years there are droughts that add to this stress. One such year was 2007, and yields were down substantially—about 50 per cent of their normal level. In such years, access to adequate dam and/or bore water is needed if yields are to be maintained and young vines protected from water stress.

Mature vines on sites with deep clay loams do not generally need supplementary watering to produce commercial dryland yields, unless very dry or drought conditions prevail. Growers usually provide dam storage for watering purposes, with many using supplementary bores as well.

Frost Considerations

Another critical factor in site selection is frost damage. The spring months of September to November can be subject to frosts and the grapevine is particularly susceptible to frost during bud burst. Depending on the variety and the location, this can have devastating consequences. Early varieties such as chardonnay, pinot noir and sauvignon blanc, in particular, need to be on frost-protected sites where there is good air drainage if such losses are to be avoided.

Winds

The District is prone to strong southerly winds in spring, which can damage emerging buds, so good wind-protected sites are preferred. Conversely, as noted, cooling easterly winds from the South Coast in the late afternoon in summer and autumn benefit the vines and grape maturation in the District.

Soils

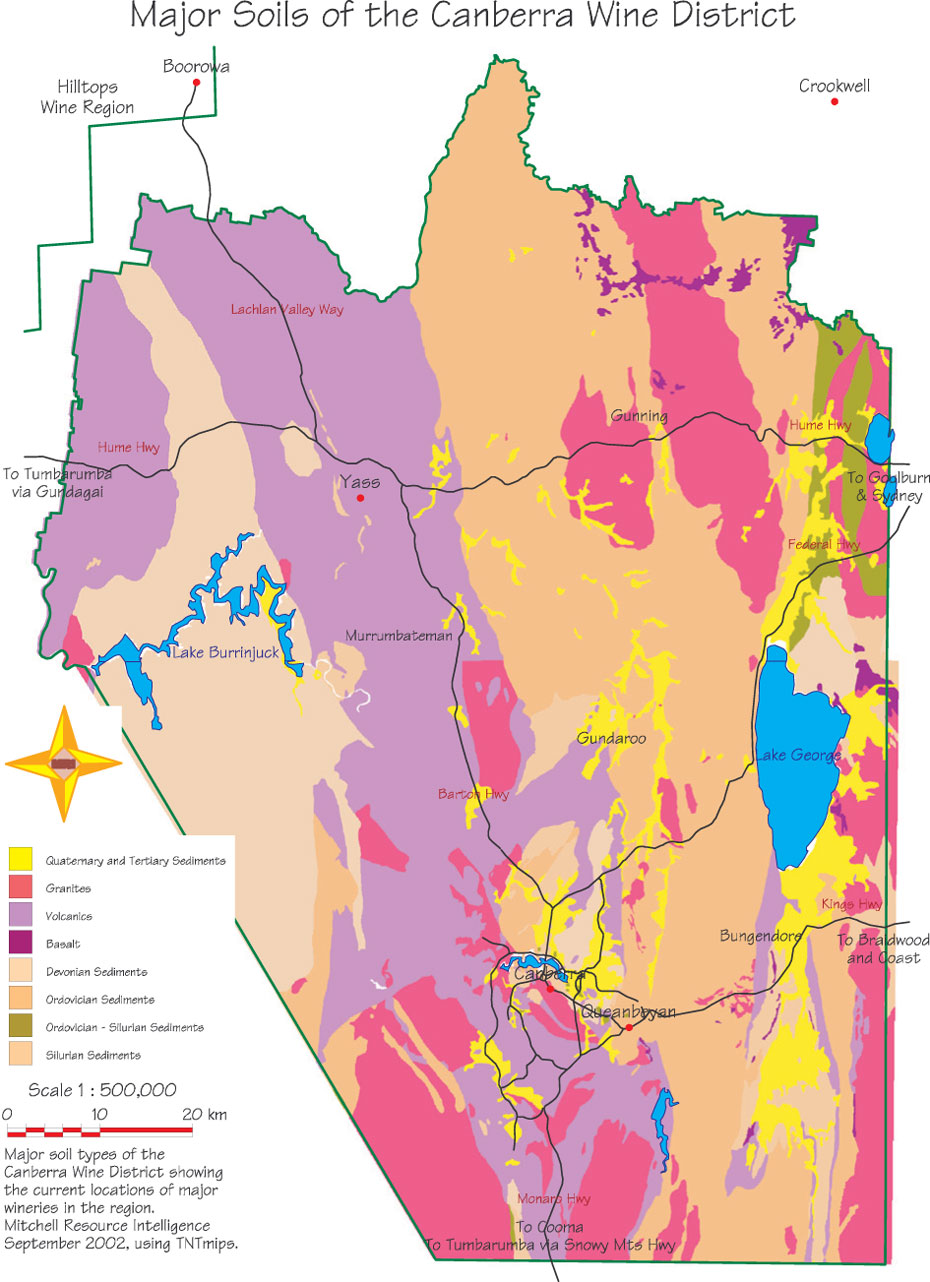

The soils of the region are complex, variable and ancient. The prime groups are ancient granite-based soils, volcanic-based soils and various shale-based sediments (ERIC 2002). The soils are often duplex, with distinct A and B horizons, with a sandy loam surface over a clay loam subsoil.

ERIC mapped eight soil classes and these are shown in Map 3. The most widespread soils are the various sediments, followed by volcanic soils and, third, the granites. They are not highly fertile soils and mostly are quite well suited to grape production.

ERIC also examined the suitability of different soil types for grape growing against the following criteria:

- good drainage and soil texture

- good water-holding capacity at depth

- low to moderate fertility

- a pH between 6 and 8.

It concluded that the volcanic-based soils, which are widespread throughout the District, are the most suitable because they generally have better drainage and aeration, with a moderately deep sandy loam over a deeper clay loam. Once the vines penetrate into the deeper clay base, they are moderately drought tolerant.

The granite-based soils are less favourable due to a higher clay content in the B Horizon. The sedimentary soils that are widespread are also suitable, but also might have a higher clay content in the deeper soils, which can impede drainage. There are also a few unusual sites—such as those on the edge of Lake George, which are relatively deep, unsorted colluvium sediments, which are also well suited to grape production.

References

CSIRO and Australian Bureau of Meteorology (2007) Climate Change in Australia, CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology through the Australian Climate Change Science Program, Melbourne, http:/www.climatechangeinaustralia.com.au/resources.php

Webb, L., G. Dunn and E.W.R. Barlow (2010) “Viticulture”, in C.J. Stoks and S.M. Howden (eds), Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: Preparing Australian agriculture, forestry and fisheries for the future, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.